You can hold your phone in front of a fern and get an immediate plant i.d. Take your device into the forest at springtime, push a button to broadcast a cardinal’s song, and another cardinal will swoop into view. Type “turkey tail mushroom” into your browser and 21,100,000 results surface.

So why sit for hours, paper and pencil in wet hands, rain creeping through the seams of your slicker, crouched and tired, all to draw a twig?

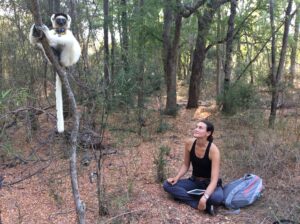

Maine Coast Semester alumni know the reason why.

In their science course, “Natural History of the Maine Coast,” students draw directly from nature every week, often twice a week. Every student is both artist and scientist; the class cannot bifurcate into artsy kids and science nerds. Roger Tory Peterson (1908-1996), the renowned wildlife artist and author who developed Camp Chewonki’s nature program, would be proud.

“There is usually some initial resistance to the drawing requirement,” says Eric McIntyre, who leads the course with his colleagues Megan McOsker, Katie Curtis, and teaching fellow Hannah Ryde. A few students always insist at first that they cannot possibly draw. “We reassure them that we want them to begin wherever they are with their drawing and develop it further,” he says.

McOsker adds, “We tell them we are liberating them–they only have to draw what is front of them.” No imagination or invention required; just deep looking. “They gain confidence as we go on,” she says.

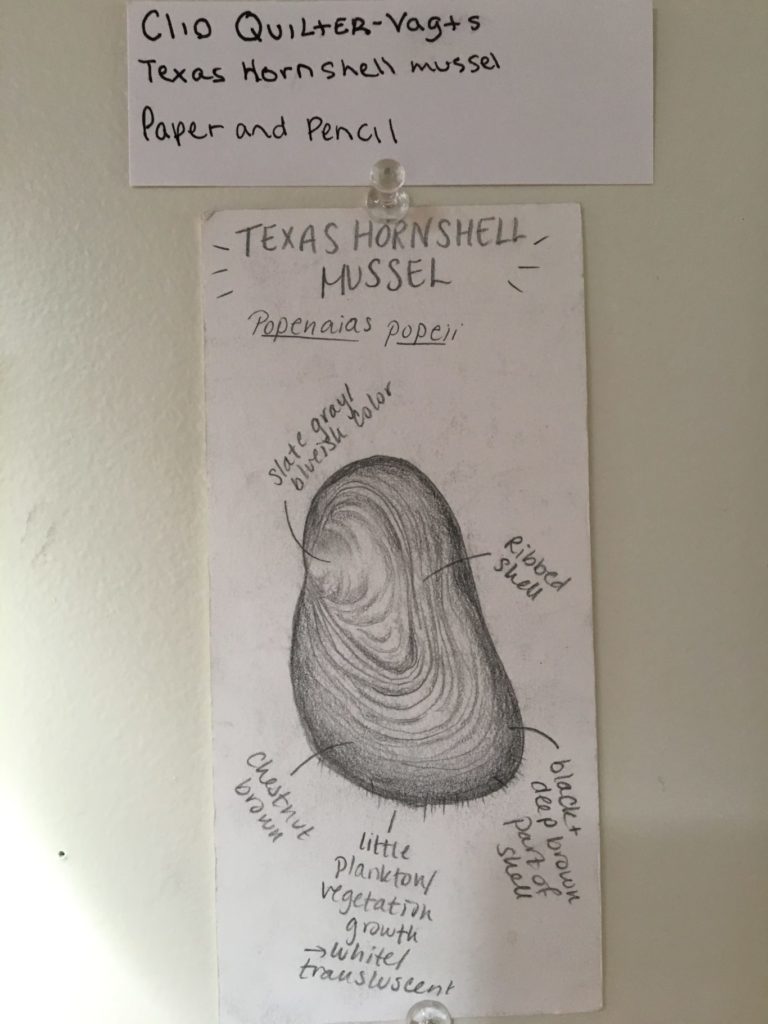

At the beginning of the course, McIntyre provides introductory training in illustration, helping students develop a sense of proportion, outline basic shapes, and refine with details. “As much as possible,” he explains, “we de-emphasize making a beautiful picture and instead emphasize accurate representation. We want them to create drawings that someone else could use to identify what they saw.”

As to why their students are asked to hunker down in any weather to record what they see around them, “We do it for a couple of reasons,” says McIntyre. “First, drawing is a way to document in the field. It is an important kind of data. What is seen with your own eyes counts.”

Second, drawing “builds the muscle of observation,” says McIntyre. “The exact shape of a bird’s bill; every point of a crab carapace–those details are easy to gloss over until you have to draw them”

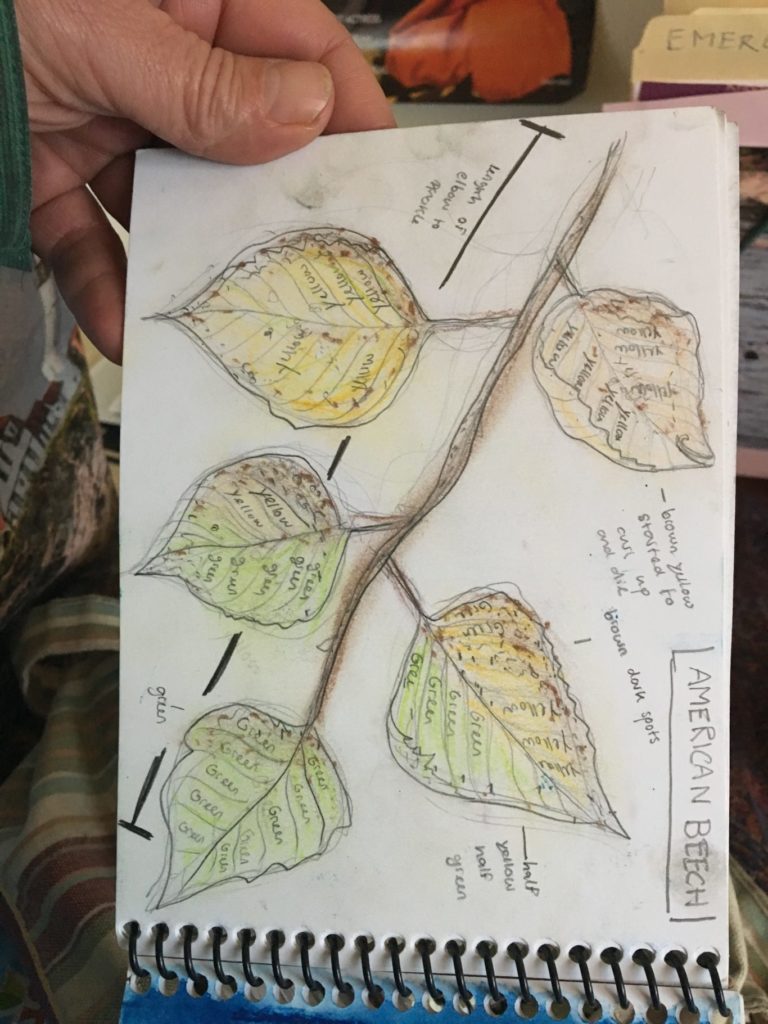

“A good example is the branching of twigs,” says McOsker. “Twigs can have opposite or alternating branching. You don’t necessarily notice or appreciate this until you have to look very closely. Observation can be an incredibly rich experience, leading to being able to perceive both details and patterns…Mastery of that is a big step toward strengthening your ability to see what is around you.”

McIntyre, Curtis, McCosker, and Ryde asked Semester 63 students to do this again and again in the yellow field journals they carry during weekly science field trips and in the notebooks they take with them to their phenology spot, a specific Chewonki Neck site assigned to them where they go repeatedly to observe cyclic, seasonal changes in nature.

They do this in all kinds of weather–cold, hot, wet, windy, McIntyre and McOsker say this is another benefit of learning to draw outdoors: “The students learn to tolerate adversity,” says McIntyre. It’s an asset they can use in many other outdoor (and indoor) adventures.

While students’ artistic endeavors in “Natural History of the Maine Coast” connect them deeply to the peninsula where they are spending four months, they are also developing their ability to perceive and appreciate the natural world wherever they go. Whether or not they ever draw from nature again, they will be better at discerning the rich details of their environment. That makes life more interesting.

McOsker and McIntyre share one more reason why they teach their science students to draw. It slows them down. It pulls them out of cyberland and right to the spot where they are breathing. It forces them to engage intimately with nature, nudging them toward answering the big question, says McOsker: “How are they going to be transformed by Chewonki?”