Traveling back and forth to a remote research outpost on another continent, climbing tall trees to send texts and emails, recording and observing countless hours of behavioral data, and collecting hundreds of poop samples for genetic analysis – these are just a few of the ways Maine Coast Semester at Chewonki science faculty, Chloe Chen-Kraus, has pursued her love of lemurs.

Chen-Kraus has always loved animals (she’s a huge Jane Goodall fan). She started her career in animal science at the College of the Atlantic in Bar Harbor, ME, where she researched small mammal behavior on Maine islands. Feeling a tug to study primates, Chen-Kraus reached out to various primatology professors to see if any graduate students needed a summer assistant. It wasn’t long before she found a taker. Soon she was immersed in a two-month internship studying the hormonal underpinnings of female dominance behavior in lemurs at the Duke Lemur Center in North Carolina.

Lemurs are fascinating animals, but few people want to spend hours upon hours carefully watching them. Not Chen-Kraus. She was completely hooked by the end of her internship. And she saw important work to do. Lemurs are the most endangered group of primates on the planet due to human encroachment and habitat loss. So, she dedicated herself to studying their ecology and conservation.

Within a year, Chen-Kraus’ passion for primate conservation led her to begin a Ph.D. at Yale, which lasted six years. She conducted behavioral research in six-month clips at a rural research and conservation area in Madagascar. The work and distance were challenging. Chen-Kraus recalls aching for far-away friends and family. On one occasion, she became terribly ill and could not easily access medical care because of her remote location. Thankfully, her research colleagues nursed her back to health, and over time the Madagascar group bonded into their own sort of family.

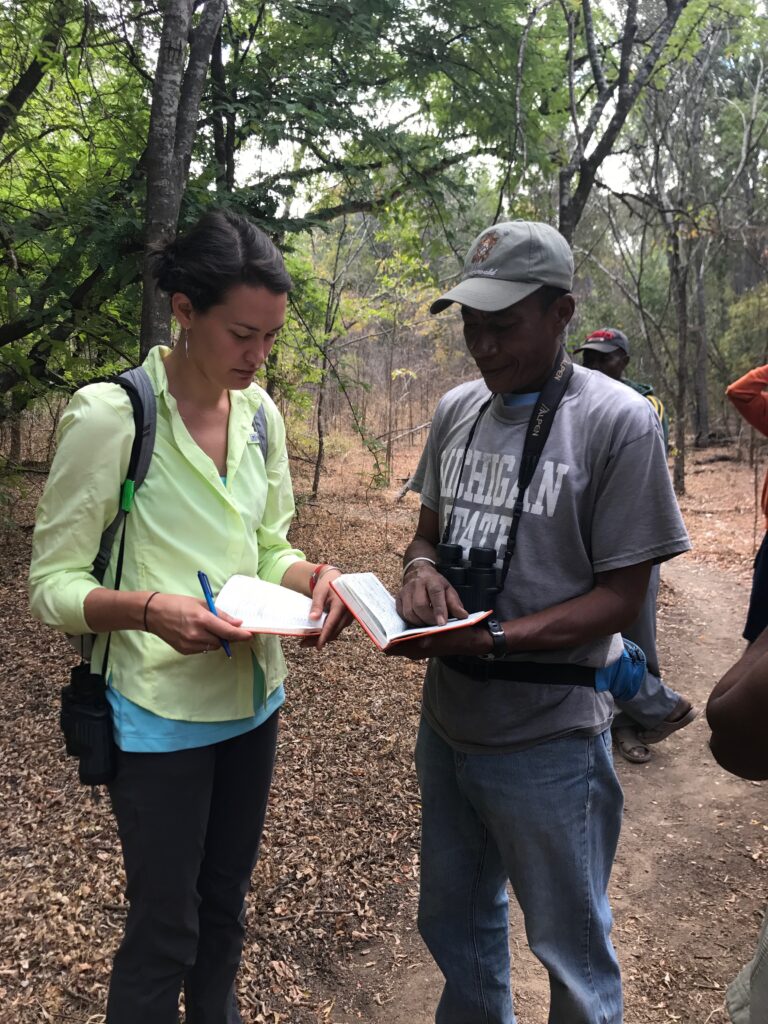

All the while, Chen-Kraus tracked and observed lemur behavior within and outside the area’s conservation zone, asking questions like – does human activity affect lemurs? How do lemurs react when confronted by people and domesticated animals? Where do lemurs occur outside the protected area? How genetically diverse is the regional population?

Chen-Kraus says she was fully expecting “doom and gloom,” but her study results were surprisingly hopeful. Although humans and domesticated animals can scare lemurs, these interruptions don’t impact their overall activity budget. In other words, the lemurs resumed their normal activities, like feeding soon after the disturbance dissipated.

Chen-Kraus also found lemurs in all forest fragments she and her team surveyed. No scientific studies had looked at lemurs in the region outside the protected area, so this work felt particularly promising. Lemurs were even active in areas frequently used by peoples, indicating that our two species can coexist.

She also found more gene flow between lemurs living in different forest patches than expected, indicating that although the population was shrinking, it still contained healthy genetic diversity. This could change as habitat loss reverberates through more generations. Still, the finding is a glimmer of hope.

Chen-Kraus spent her last year at Yale analyzing her research, writing her P.h.D. thesis, and teaching. After graduating, she spent one more year at Yale as a lecturer. Then, it was time to move on. She had fallen in love with teaching but felt stymied by the traditional classroom environment (no big surprise for someone who loves to spend hours watching animal behavior). Chewonki seemed like a great option.

Now, Chen-Kraus finds joy in hands-on explorations with students at our campus streams, ponds, forest, and marshes. “I love seeing that spark of intense curiosity and wonder about the natural world in my students,” she says. During a recent field lab, her students collected and observed tiny lifeforms from a nearby stream. One said, “I feel like a child again.” How wonderful is that?

Chen-Kraus hasn’t stopped loving lemurs or studying how to conserve their species, either. She returned to Madagascar this summer to visit her research family, helping them with long-term monitoring efforts. She says that spending time there is like returning home.

Thanks for sharing your passion for the natural world with our students, Chloe! We couldn’t be prouder to have you on our team.