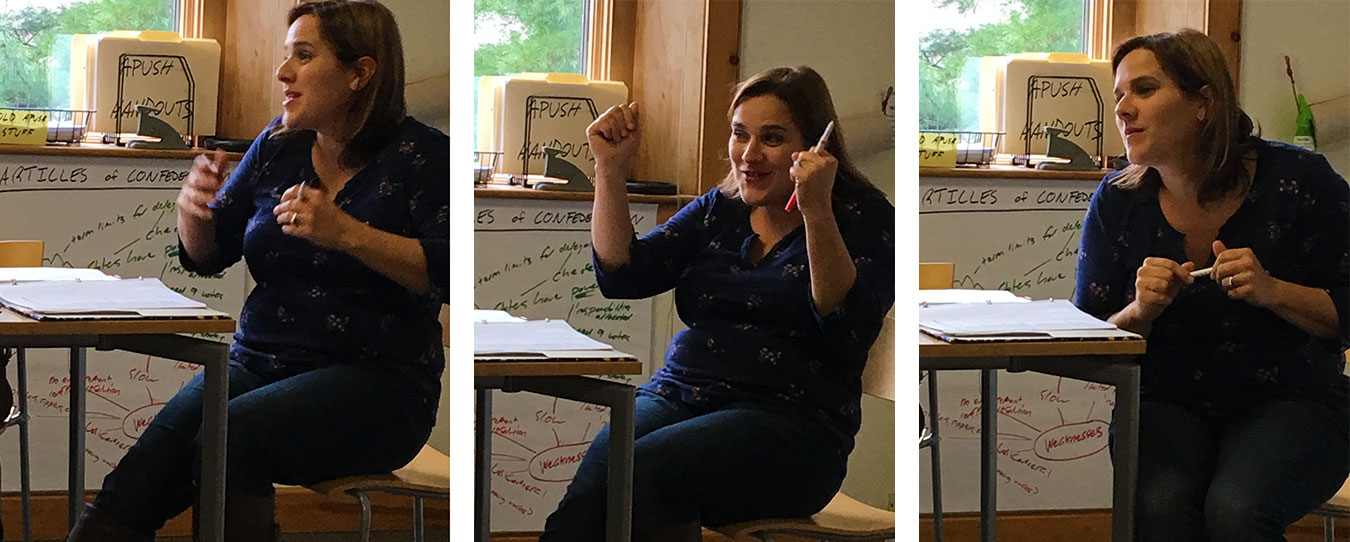

C’est élégant. C’est élastique. C’est fantastique. C’est la langue française! And it pours from Esther Kary, Maine Coast Semester at Chewonki teacher of French. Standing before the class, her hands are in motion; her eyebrows arch over flashing dark eyes; she shrugs, coaxes, purses her lips; her voice rises and falls. In every way she can, in ways that seem, well, very French, Kary encourages her students to wade into the fast-moving silver stream that is French.

Most Maine Coast Semester students take French or Spanish; some study Latin or Chinese; a handful, Greek or German. “I love all languages,” says Kary, but, with apologies to her fellow language teachers here, she believes “Chewonki is an incredibly wonderful place to teach and learn French” because of the strong influence of French-Canadian culture in Maine. Her language curriculum is “all place-based,” she says, and that includes Kary herself: she grew up in Québec, which shares history and geography with Maine. She is proud of the heritage she carries in her voice.

This morning she writes a French tongue-twister on the board and leads the class in practicing it, then asks each student to say it on her or his own for everyone else to hear. Some stumble as they work their way through the linguistic gymnastics, but they all persist. She praises their pronunciation and explains why the final “e” in some words is a spoken flourish while in others it sits quietly.

Each week, a student brings a song in French to share. This week, it’s “Alors On Danse” by the Belgian rapper Stromae. The class listens, reads the lyrics, and then discusses the meaning, searching for proper tenses, verb agreements, and the musical sentences Kary models.

“Oh, Madame, Madame!’ calls out Vinny Langan (from New Jersey and the Thacher School). “Eh bien, Vinny?” says Kary. He makes his point, inserting an English word here and there when he can’t retrieve the right French one. She corrects but does not squelch him.

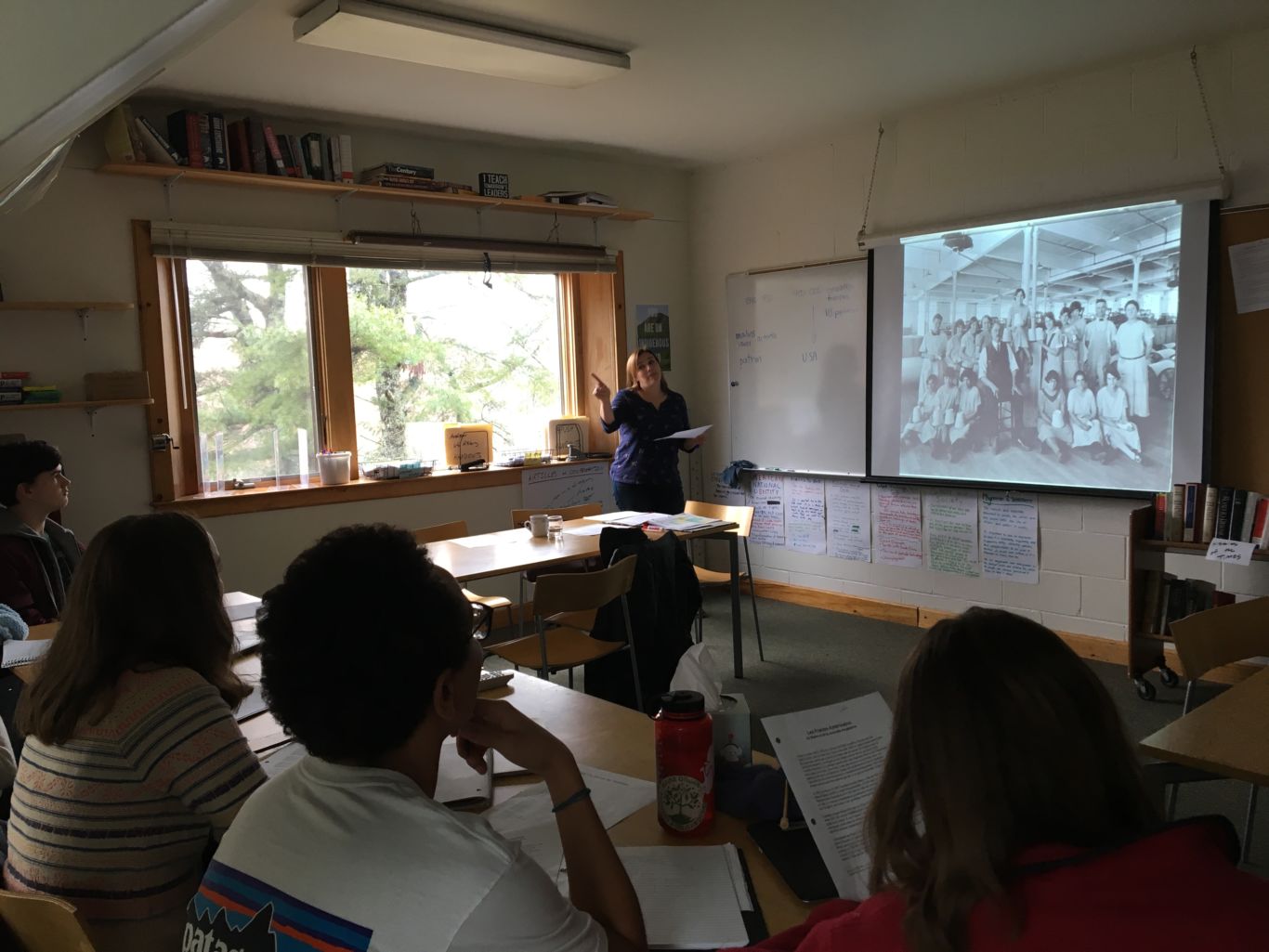

Next Kary turns to a discussion of Québec’s historical relationship with Maine, which began with the explorers, trappers, fur traders, and missionaries who arrived in the 17th and 18th centuries. Competing with the English, French-Canadians formed alliances with Native Americans, with whom they fought (and eventually lost to) the English throughout the region, including the midcoast area that is Maine Coast Semester’s home. By the mid 19th century, French-speaking, Catholic Canadians were predominantly farmers. Between 1840 and 1930, however, about 900,000 French-Canadians migrated south, abandoning agriculture to take advantage of the Industrial Revolution sweeping New England.

Seeing Kary write moulins (mills) on the board, Vinny raises his arms and calls out “Moulin Rouuuge!” Not exactly. These moulins produced textiles with the hard work of newly arrived French-Canadians, many of them women and children. They flocked to Maine mill towns like Lewiston, Waterville, Augusta, and Brunswick, along rivers that powered the huge weaving machines.

In their new life in Maine, explains Kary, French-speaking immigrants established “Petits-Canada,” communities determined to maintain their language and traditions despite Protestant Mainers’ disdain. Tensions rose and the newcomers suffered “beaucoup d’intimidation,” says Kary. Speaking French became illegal and children were punished if they used it at school. Within one generation, the desire to assimilate swept away many French-Canadian traditions. French names often morphed into English translations (Lejeune became “Young,” Leblanc became “White,” etc.).

Yet French survived in Maine, and in recent years it’s been enjoying a revival, partly because of growing appreciation for cultural differences and also because of an influx of immigrants from French-speaking African countries. Each semester, Kary takes her students to the Franco-American Heritage Center in Lewiston. There, people of French-Canadian ancestry, many of them elderly, mix with each other and mostly younger African immigrants to use and celebrate the language they love. Kary and her students join the gathering, share the meal, and get a chance to practice.

“It’s a wonderful opportunity for my students to hear the language and other people’s stories,” says Kary. Sometimes the older people are shy about speaking to the students, but once they realize the students genuinely want to engage in French, conversation flows.

Kary’s French classes have been known to cook special meals like chicken Basque and chocolate mousse for the Maine Coast Semester community. Inside and outside of class, Kary uses food, conversation, music, literature, works of non-fiction, and history to expose her students to French culture. “Otis does the same,” she says of Spanish teacher Otis Wortley. “We believe in immersion.”

Today, if you love French, Kary says, embrace every iteration, from Creole French in the South to Acadian French in Eastern Canada. “A well-rounded French speaker can understand the French spoken in Québec and the Congo as well as Paris,” says Kary. “It’s a matter of fine-tuning your ear and appreciating it all.”

Kary and her husband, Maine Coast Semester science teacher James Kary, live at Chewonki with their children, Aiden and Cecilia. The couple tries to use her first language with them but “since they’ve started school, it’s difficult to get them to use it,” she says. The Karys make a point of visiting her family in Québec often to keep the language strong.

Le chance de la vie may have taken Esther Kary out of French Québec. Nothing can take French Québec out of Esther Kary.