Cullen: I’m talking today with Robbin Dilley, our Natural History and Ecology Teacher at Maine Coast Semester. Robbin, can we start out with a 30-second life story? How did you become a science teacher?

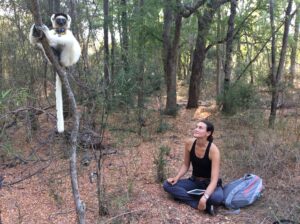

Robbin: Sure! I studied biology at Columbia and originally wanted to go into environmental law. But the more I spoke with lawyers, the more I realized how long it takes to see meaningful change in environmental policy—decades, sometimes. After college, I worked for Outward Bound, then did seasonal field research—studying whales in Gloucester, MA and working in Volcanoes National Park in Hawaii. I saw that even in science, there was a huge delay between data collection and policy change. But working with high schoolers through Outward Bound was immediate and energizing. I loved it. So I joined the Boston Teacher Residency, a program similar to the Maine Coast Semester Teaching Fellowship program here, and discovered how much I love teaching science—especially when students get to ask their own questions and do their own investigations.

Robbin: Sure! I studied biology at Columbia and originally wanted to go into environmental law. But the more I spoke with lawyers, the more I realized how long it takes to see meaningful change in environmental policy—decades, sometimes. After college, I worked for Outward Bound, then did seasonal field research—studying whales in Gloucester, MA and working in Volcanoes National Park in Hawaii. I saw that even in science, there was a huge delay between data collection and policy change. But working with high schoolers through Outward Bound was immediate and energizing. I loved it. So I joined the Boston Teacher Residency, a program similar to the Maine Coast Semester Teaching Fellowship program here, and discovered how much I love teaching science—especially when students get to ask their own questions and do their own investigations.

Cullen: Had you done field-lab-style teaching before coming to Chewonki?

Robbin: Yes, it’s actually pretty similar to the field research I did post-college. In traditional biology programs, especially at the AP or undergrad level, the focus is often on cellular or molecular biology. Field science—like working with sea turtles or whales—felt completely different. Here at Chewonki, we’re giving students access to a kind of science that’s often hard to come by in formal education.

Cullen: I’ve seen that spark in students here too—especially when they realize they are collecting the data, not just reading about someone else’s results in a book.

Robbin: Exactly. And what’s great about natural history is that it starts with observation. It’s accessible. You don’t need a fancy lab setup—you need curiosity. Some field labs involve data collection, but others are like Jane Goodall-style observations. And the more closely you look at something, the more interesting it becomes.

Cullen: How do you teach that? How do you get students to look more deeply?

Robbin: It takes practice. A student might look around and say, “There’s nothing here,” even though we’re in the middle of a forest—because they’re expecting to see something big, like a moose. So we use prompts like “zoom in, zoom out,” where students first look at something big and then examine it closely—say, a tree that’s actually home to dozens of mosses and lichens. We also read authors like Robbin Wall Kimmerer and Bernd Heinrich, who model this way of seeing—of asking questions, noticing patterns, and slowly piecing together clues from nature.

Cullen: I’ve noticed students all have bright yellow matching field journals – what role do those play in the field labs?

Robbin: In most field labs, students record “Qs and Os”—questions and observations. We guide them to notice what’s distinctive about a place, for example Pemaquid Point’s intertidal zones or geology. Instead of just writing about the sky or ocean, we want them to really dig into the specific unique features. They use sketches and writing to record what they see in a way that someone else could understand the data without being there. The goal is precision—using multiple senses, accurate detail, and curiosity.

Cullen: It seems there’s a neat overlap with art class there, too, I’ve visited the student art show at the end of the term and those field journal drawings are right alongside the other artwork.

Robbin: Definitely. Students with a strong art background might make a beautiful drawing of a leaf—but it might not be scientifically useful. Others might not see themselves as artistic, but they learn to make incredibly detailed, accurate observations. It opens up a cool conversation about different kinds of seeing and documenting.

Cullen: Do you know Roger Tory Peterson sketched the first draft of Field Guide to Birds right here at Chewonki in the 1930’s, behind the farmhouse?

Robbin: It’s such a good reminder that the boundaries we draw between disciplines—art, science, observation—are often artificial.

Cullen: What’s been the most challenging part of teaching field labs?

Robbin: Planning! Everything depends on season, tide, temperature, sunset, and weather. A wind advisory can cancel a forest lab. So the curriculum is backward-designed from those field opportunities. It’s one of the best parts of the program—labs are tied to what’s actually happening in this place, right now—but it takes careful coordination.

Cullen: And what would you say is the best growth opportunity—for students?

Robbin: It varies. For students used to indoor labs, fieldwork can be a shock. You’re muddy, it might be snowing, and you’re racing the tide or sunset. You can’t just “come back later.” But that’s what real field science is—it teaches flexibility, adaptability, and awareness of natural rhythms.

Cullen: Is there a moment you wish every student could experience?

Robbin: Yes. We were wrapping up a stream field lab and a student said, “I’ve been around streams my whole life, but I never knew there was this whole world inside them.” That moment of seeing the familiar with new eyes—it’s transformative. That’s the power of connection. When students see, really see, and realize they’re part of a living system, it changes them. That’s the kind of learning that stays.

Cullen: That’s what place-based education is all about. Books are the abstraction— the mud is the real thing.

Robbin: Exactly. Put your hands in it.

Robbin Dilley is the Natural History and Ecology Teacher at Maine Coast Semester, and Cullen McGough is the Director of Communications at Chewonki.