Indigo blues, that is.

This summer and fall, participants in programs across Chewonki – from Boys Camp to the Elementary School to the Maine Coast Semester – have been dyeing cotton fabric and farm wool with Japanese indigo. This plant, carefully cultivated on the farm since we seeded it indoors in early April and transplanted it into the dye garden in late May, thrived this year in our hot summer and fall. Looking at the green leaves of this annual plant, you’d never guess the blue that hides within.

Indigo is one of many plants that we grow on the farm for natural dyeing. Marigolds and coreopsis make brilliant yellows, while goldenrod wild-harvested from the farm edges create a more neon yellow hue. Black walnuts make a rich brown, onion skins a tangy orange, and black hollyhocks a subtle grey to lavender (depending on your dye concentration and the pH of your water). After two years of patiently cultivating madder, we’ll harvest the roots for the first time next spring and cross our fingers for red.

Oh, but indigo: it’s like magic. Or chemistry, depending on how you fall on the magic-to-science continuum. Here are the details of the process, for all you scientists: We carefully and slowly heat water and Japanese indigo leaves to 160 degrees over a two hour period before straining out the leaf matter. The remaining liquid is made alkaline through the addition of baking soda, and then we pour the liquid back and forth from one pot to another to add oxygen. We add a reducing agent called thiourea dioxide, stirring carefully to incorporate it throughout the liquid without adding much more oxygen, and then we let the solution sit for one hour. At that point, it’s fine to oh-so-carefully add our wet cloth or yarn, again trying to disturb the dye bath as little as possible. Twenty minutes later, the underwater material looks a particularly unappealing shade of yellow-green until you pull it out of the dye bath. As oxygen hits it – voila! – you have an instant blue.

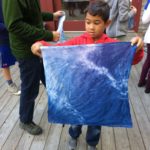

I have never pulled something out of an indigo dye bath without hearing gasps, whoas, and whoops from the people around me. It’s a striking transformation. Exhibit A: Check out the expressions on the faces of the two campers on the far right of this photo (one young man is so excited that he’s buried his face in his hands!).

Boys campers and elementary schoolers experimented this year with shibori dyeing, a traditional Japanese dyeing technique that employs all sorts of materials and approaches – rubber bands, pleats, twists, compressions, clips, wood, posts – to create resist, leading to swirls and patterns in many shapes and sizes.

Meanwhile, the semester students dove into a morning of homesteading skills a few Saturdays back. While some students dyed farm wool with a range of wild and cultivated plant materials and engaged in other fiber arts (including weaving and felting), others made cheese, kimchi, and sauerkraut; carved spoons; learned basic embroidery; made books; and mixed up homemade soap with farm pig lard as a base.

Creativity abounds as students continue to engage their hands in these newfound skills. Just today, I watched a student claim his naturally dyed skein of farm wool, saying as he walked away, “Now I just need to learn how to knit.” Yes!