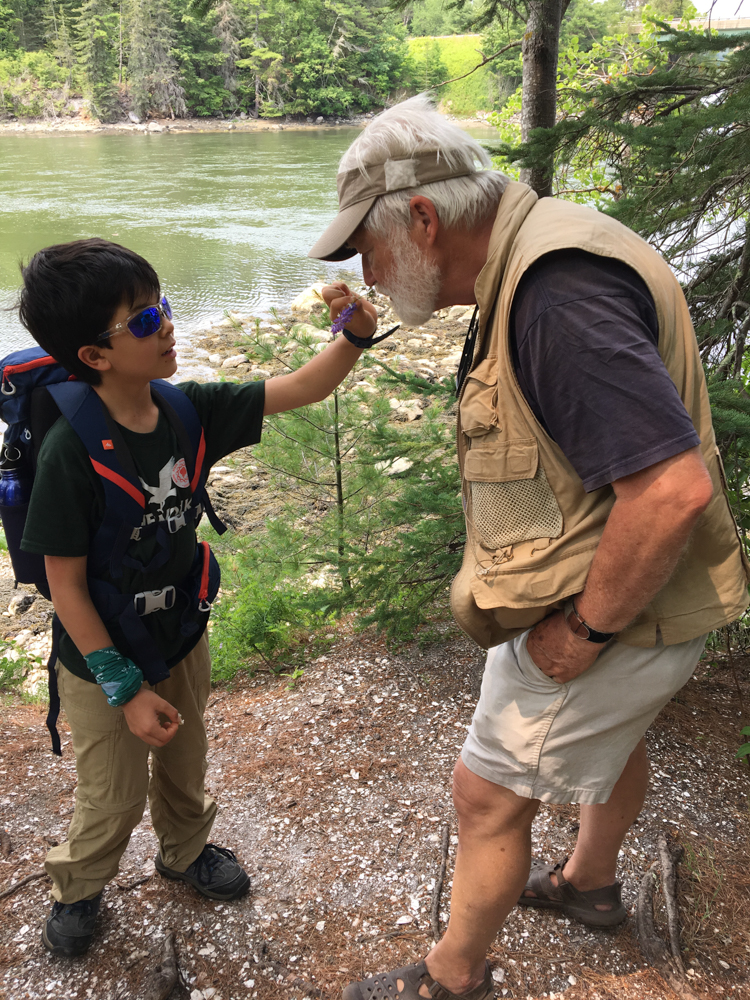

Since 2007, “Doc Fred” Cichocki has been the pied piper of natural history for Camp Chewonki. A dignified cross between the eminent biologist E. O. Wilson and a rakish Shakespearian bard, Cichocki cuts a stately figure with a full white beard and mane of hair. On campus, he’s distinctive in his khaki vest (replete with pockets and pouches stuffed full with flora and fauna) and can usually be found carrying a “natural history mystery” gently dislodged from somewhere in Chewonki’s woods, waters, forests, and fields. Even more noticable is the perpetual train of curious campers at his elbow, asking, “What’s that? Where’d you find that? Can I touch it? Doc? Can I?”

Cichocki, a retired professor with advanced degrees in ecology and evolutionary biology, leads the nature program at Boys Camp. He does so with intellectual passion, persistence, and Zen-like calm, maintaining his cool even in a maelstrom of excited campers. He has seized upon the great Chewonki tradition of teaching young people to appreciate and understand the natural world around them– algae, seaweed, ants, sap, fish, frogs, wildflowers, bees, trees, and so many other things that feel especially close at camp.

Life is interesting when you hang with Doc Fred. Most days, he presents a Natural History Mystery to campers and counselors each day at lunch. He shares some biological details and a few clues; then it’s up to the campers to identify the mysterious specimen within 24 hours. The winner is announced the following day.

Cichocki also creates the Nature Scavenger Hunt, which sends the whole camp running, climbing, scrambling, and snooping all over Chewonki Neck for species and sites he wants them to examine.

When Cichocki is not outdoors, he might be found in Chewonki’s Nature Museum, a standalone shingled building with humble beginnings a chicken coop, but was refashioned in the early 1930s by one of Chewonki’s first nature counselors–and later, renowned ornithologist and artist—-Roger Tory Peterson to serve as a studio. It has been natural history headquarters for camp ever since.

On Tent Days (special activity days when campers get a chance to leave the Neck for local adventures), Cichocki often takes ardent young naturalists on field trips around midcoast Maine. This past week, with 11 campers in tow, he set out for the Maine State Aquarium, on the nearby tip of the Boothbay peninsula.

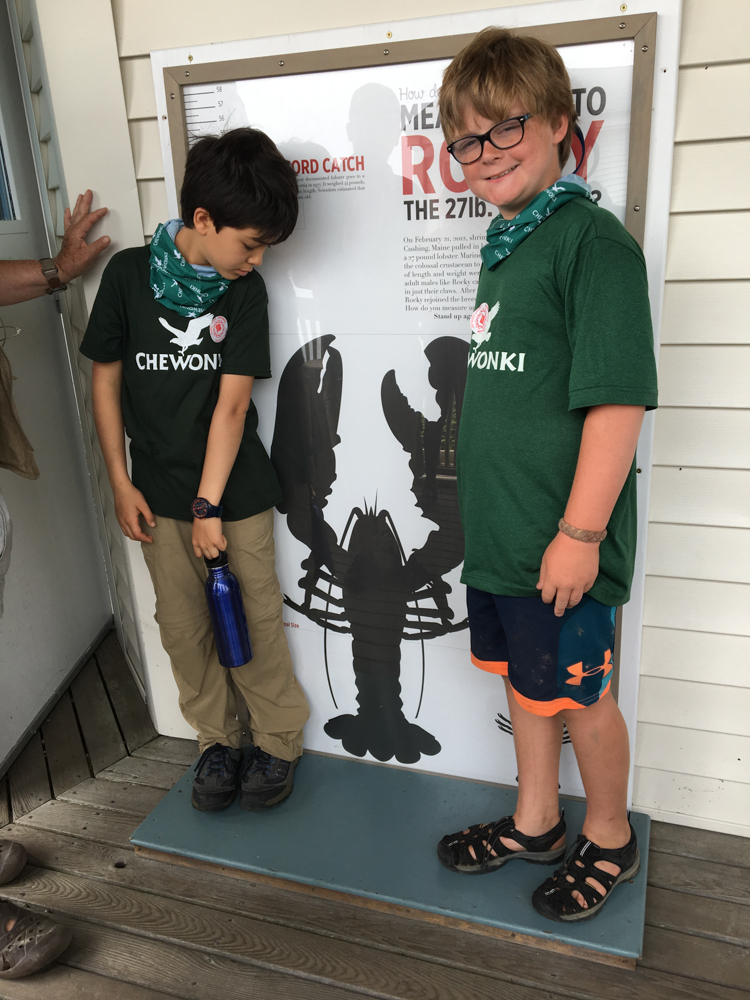

There, glowing green water tanks held samples of Maine’s native marine population. Two open tanks gave the campers a chance to touch sea cucumbers, hermit crabs, starfish, horseshoe crabs, a shark, a skate, and more. They learned about lobsters and got a close-up look at several live lobsters including a blue one, one missing its crusher claw but growing a new one, and a bi-color lobster, half orange, half brown.

Doc Fred pointed out the lobster trap display and the painted silhouette of a 27-pound lobster before everyone boarded the van and headed to their next stop: Damariscotta’s oyster shell middens.

As the boys stretched out on the grass to eat lunch under a tree, Doc Fred told them, “Gentlemen, you are near the site of the largest Indian midden in the Eastern United States. It was discovered in 1692, filled with the shells of massive oysters that no longer exist here.”

To reach the midden’s remains, Cichocki and the campers followed a path through fields of blooming vetch, milkweed, dogbane, knapweed, and other plants.

“Goldfinches love knapweed seeds,” Doc Fred explained, “but it’s an invasive plant that pushes native plants out of their place.”

One boy spotted a monarch butterfly hovering around pink milkweed flowers. “It’s beautiful!” he exclaimed.

“Yes, and that butterfly’s babies will fly all the way to Mexico this fall,” said Doc Fred.

“Mexico? They fly all the way to Mexico?” a camper asked. “That’s absolutely insane!”

As they walked, Doc Fred pointed out other summer treasures; iridescent dogbane beetles; spittlebugs hiding in bubbly cocoons; round-leaved dogwood; wild grape; poison ivy–a beautiful, dangerous July tangle.

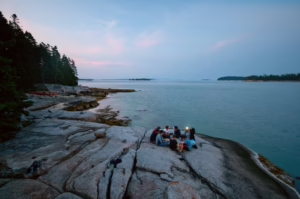

After inspecting the ancient oyster shell mound, the group set off for Pemaquid Point, where they explored tidepools. The aquarium and the shell middens “were just a teaser,” says Cichocki. “The real fun is tidepools.”

The boys explored the rockbound pools, finding lobsters, crabs, periwinkles, sea urchins, seaweed, and mussels. After heavy lobbying, Doc Fred agreed to bring a few mussels back to Chewonki, where he helped cook them so these young naturalists could enjoy a special Maine treat.

Doc Fred Cichocki takes his teaching responsibility seriously and he is devoted to instilling a naturalist’s sensibility in campers who spend a summer at Chewonki.