“Put away that umbrella,” chides Kary. “We don’t need umbrellas here!” The students laugh.

“It was hard in the beginning,” one admits, “but now we’re used to it. We love it.”

On this afternoon they are learning about succession, how lichen on granite can give way to moss, then leafy plants, then grasses, then canes, then shrubs and trees. The class gathers around a ledge, where Kary points out dark green moss, leans close to it, and asks, “Who is about to dethrone the moss here?”

Silence for a moment, then one student shouts, “Leafy plants!” A grove of mouse-ear hawkweed has elbowed some of the moss aside.

“It’s an incredibly cool way to look at the world,” says one young woman about her science course, Natural History of the Maine Coast. She’s a student at Maine Coast Semester at Chewonki. You might wonder about her enthusiasm if you saw the class gathering outside on a wet afternoon, swathed in rain gear, before a five-hour field lab.

They go on this immersive adventure every week in addition to two classroom sessions and an hour in a sit-spot they choose on Chewonki Neck for observing phenological changes large (the first snowstorm, the hummingbirds’ spring return) to small (the fragrance of tiny trailing arbutus blossoms).

“And how are these hawkweed able to survive?” Kary queries. They look like prime grazing material, but, “Even if an animal has nice lips for browsing,” demonstrates Kary, dropping to all fours and mouthing the leaves, “How does this leafy plant defend itself?” Little hairs, he reveals, make mouse-ear hawkweed leaves prickly and unappetizing.

Kary and Abuza lead the group toward a tangle of raspberry canes and pasture rose along the forest’s edge. As they walk, Abuza suddenly says, “Oh! Take a look at this dandelion. Who wants to try it?” A student pinches off part of the small leaf, pops it into her mouth, and grimaces. Bitterness is another way to repel predators.

After examining rosehips and thorns, branch tips where growth will swell next spring, and staghorn sumac, Abuza directs everyone’s attention to a red maple and a white ash; the first has thin twigs, the second, thick–an easy way to tell them apart.

Several students start jumping up and down. Abuza stops and says cheerfully, “If you are cold, run down there and back.” Most of the group gallops toward Montsweag Brook, Kary among them. They return with pink cheeks.

The course’s emphasis on natural history is unusual. Most of these students will return to physics or biology classes in their sending schools, depending on the school’s planned progression. Kary and Abuza are emphatic that what students learn here is highly relevant to other fields of science and that there is an urgent need for both scientists and lay people to understand natural history.

“Small details and incremental changes in nature,” says Abuza, “are actually exactly what scientists are focusing on now, especially in light of climate change.”

Kary says, “Students leave our course with a greater sense of awareness and an ability to observe details in the natural world and make connections between those details and what it means to be an aware, engaged citizen.”

“The natural history approach is not at odds with mainstream science,” Abuza says. “Data collection is an essential part of science and it’s a key part of the trend toward citizen scientists gathering information useful to the larger community.”

“We want the course to be more than a stand-alone experience,” Abuza puts it. “We hope our students will pull these threads forward into their lives” after Maine Coast Semester. (She has lived this experience. “It wasn’t till I came here as a student myself [as part of Maine Coast Semester 35] that I realized my hobbies and passions could become a course of study,” she says.)

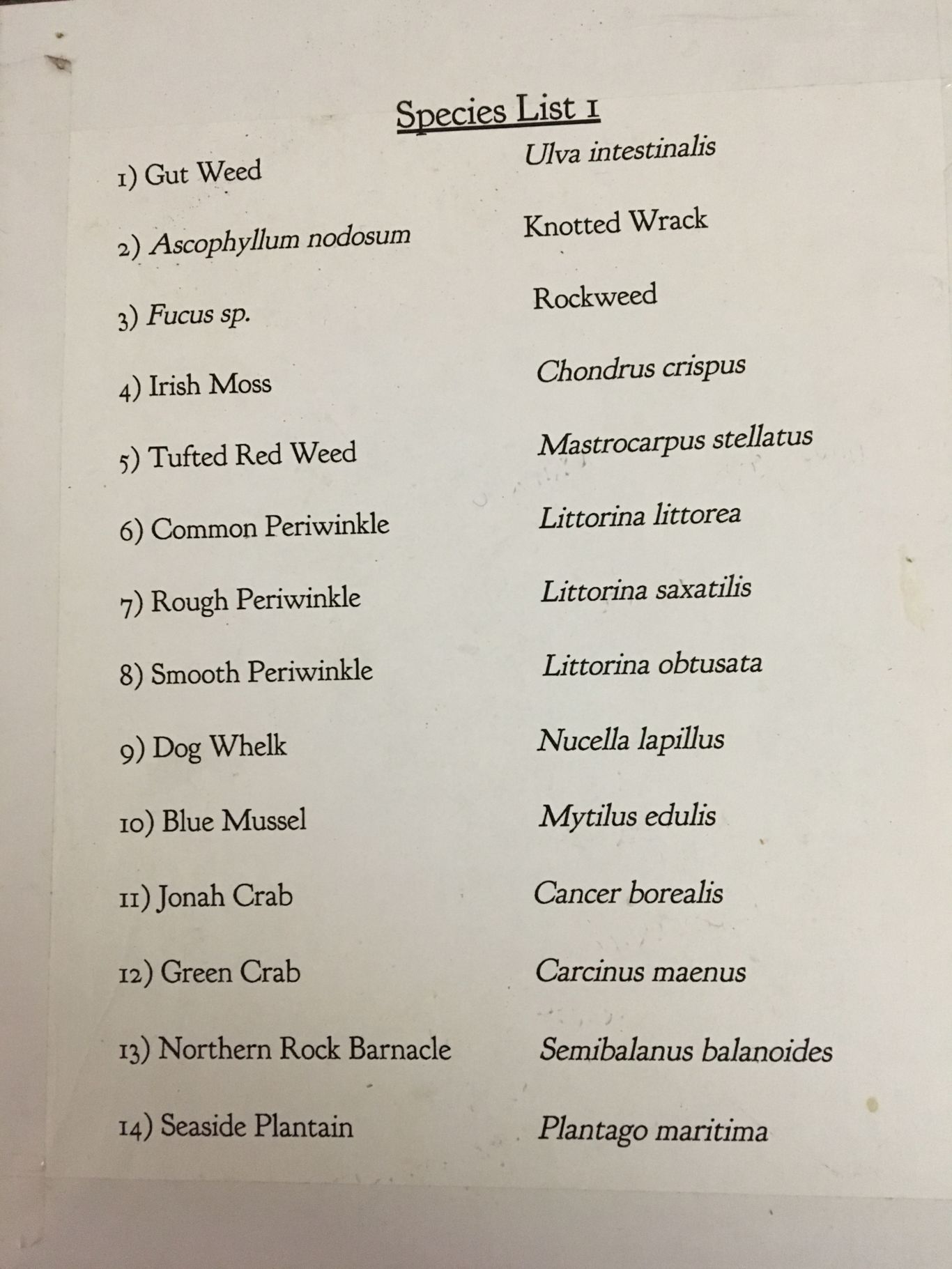

In class later in the week, students look over the last in a series of species lists, bringing to 100 the number of species they must be ready to identify in their field lab final. Then the class turns to their ongoing study of forests.

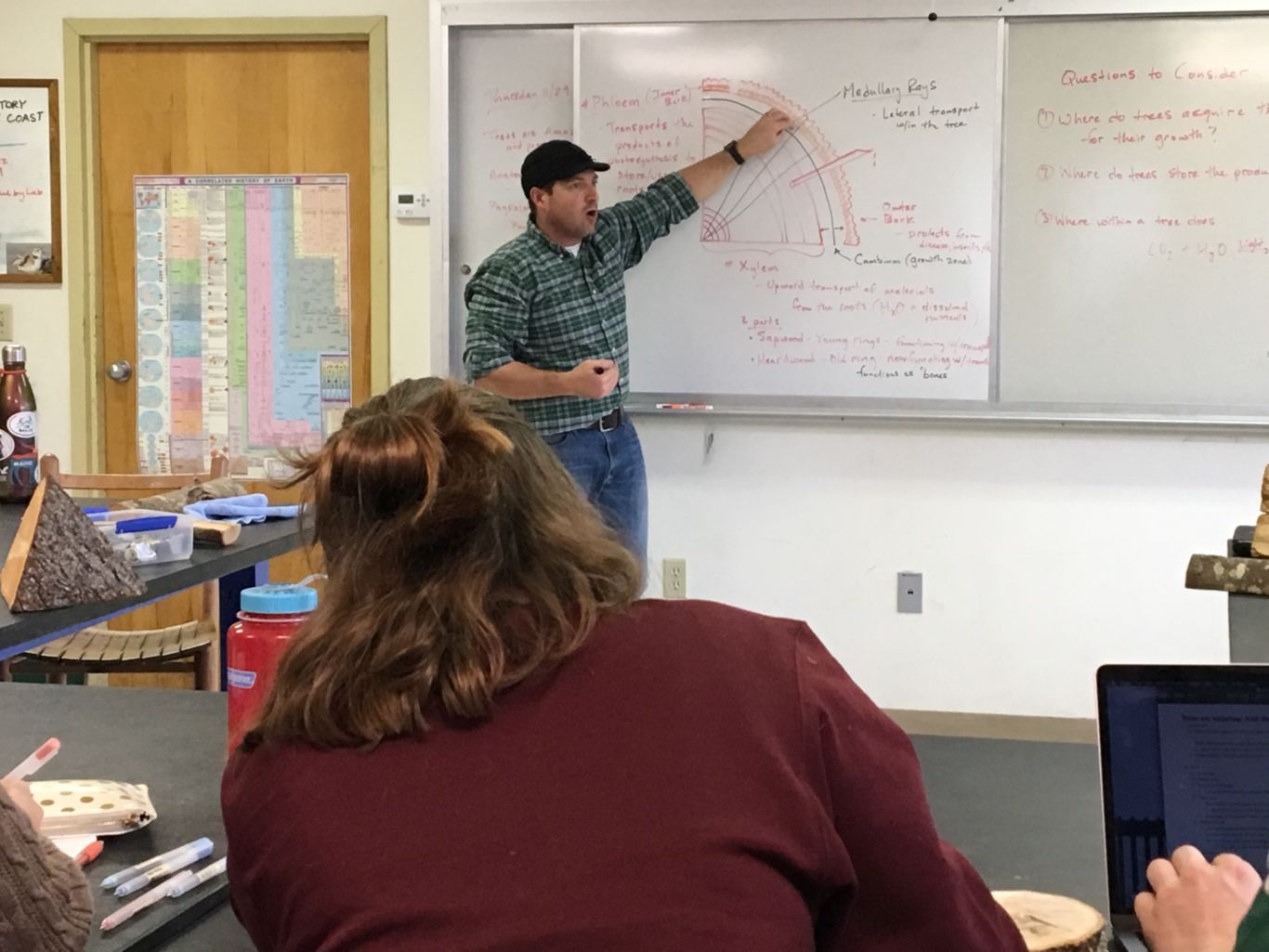

“We’re going to study tree physiology today,” says Kary. “I want to leave you saying, ‘Wow, that’s amazing.’”

On the board, he writes:

- Where do trees acquire the raw materials they need to grow?

- Where do they store the products of photosynthesis? They take things into their bodies and with those, create new things; where do those new things go?

- Where within the tree does growth occur?

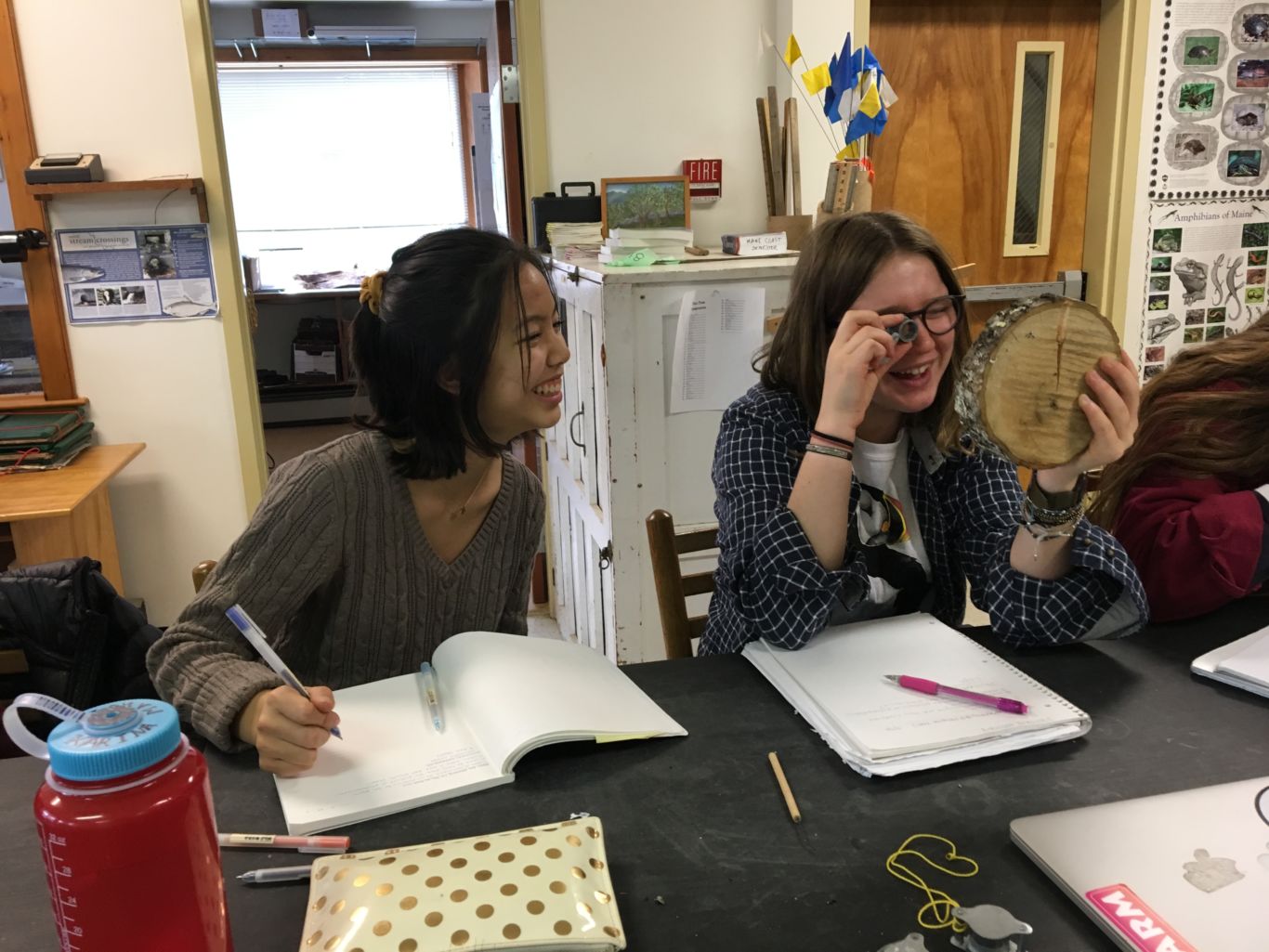

Kary passes out slices of tree trunk. “You’ll have to put aside your knitting and share a tree cookie,” he says, and two students stop knitting. With probes and a hand lens, they study the wood.

Kary: “What do you notice?”

Alex: “In between the wide lines, there are other lines.”

Kary: “Yes. There are alternating rings: some solid and others porous. The porous rings are thinner; they represent the tree’s growth in summer and fall. The solid, thicker rings signify spring growth, when the leaves have come out and begun absorbing CO2, hours of sunlight have increased, and tree roots are pulling H2O from the soil… Why are trees amazing? Because they can take thin air and turn it into mass called wood.”

“It’s a privilege and a joy to work alongside these students and explore the natural world,” says Abuza. Kary adds, “The beautiful thing about natural history is that it’s endless–you really can be a lifelong learner. Becca and I are continually learning. Teaching is a lot like bells that chime in harmony. We get to respond to the students’ curiosity and make it stronger.”

“We just had a terrific school meeting,” says Kary. “The students had to say what pieces of their Maine Coast Semester experience they are proud of or were new to them. Quite a few said, ‘Being outside’ or ‘Being comfortable outside.’ A couple even said, ‘Over Thanksgiving break, I identified some species where I was.’”

Says Kary, “That means they are seeing the world in new ways–the greatest gratification to us.”