“Things are changing, and there’s no going back. We need to go forward in a way that connects people with the land and revives traditional practices while adapting them to a modern context,” says Sarah Klain. “The metaphor of a braid is apt. We’re not mashing it all together. Each strand is distinct.”

Klain is an alumna of Maine Coast Semester at Chewonki (18), former Camp Chewonki staff member, and Assistant Professor of Environment and Society at Utah State University. For the past two years, she has been collaborating with the Northwestern Band of the Shoshone Nation to create a land stewardship plan for Boa Ogoi, a 585-acre parcel in southeastern Idaho where the US Army Cavalry and settlers massacred over 400 tribe members in 1863. Led by tribal leader Darren Parry, the Northwestern Band of the Shoshone purchased the land in 2018 to build an interpretive center and restore the pre-massacre ethos of the landscape. Klain hopes that this can be a place for the tribe–a geographically dispersed population who has never had a reservation, ”to affirm their identity, engage both tribal and non-tribal youth with NWBSN culture, and tell their story to the larger world.”

Creating a land stewardship plan for Boa Ogoi is far from straightforward, however. For generations, the Shoshone seasonally migrated to hunt game, catch fish, and gather plant foods including pine nuts, chokecherries, and roots. They often made a winter camp near the hotsprings of Boa Ogoi. In the 150 years since the massacre, however, the land of Boa Ogoi has been farmed and grazed extensively by cattle. Irrigation systems, canal-building, run-off from upstream agriculture, cattle feedlots, intensive grazing and invasive species have decimated native plant and animal populations. A stream that once provided drinking water and habitat for endemic trout now runs dark and murky. Beyond the many challenges presented by the site, Boa Ogoi also exists in a region already feeling the effects of climate change via increased temperature variability, reduced winter snowpack, and reductions in annual precipitation. The species that flourished 150 years ago may not be able to sustain themselves without intensive human intervention now or in the coming 50 years.

How does one begin to rebuild? Perhaps part of the answer is embracing the idea that no singular discipline or way of knowing can show us the way. Instead, it is only by weaving together indigenous knowledge with modern environmental science, local knowledge, a sense of history, and appreciation for human cultures that we can begin to regenerate Boa Ogoi and damaged landscapes like it.

In her 2014 book Braiding Sweetgrass, Robin Wall Kimmerer uses the eponymous practice as more than a literary device – it’s a call to action. A member of the citizen Potowatomi nation and “card-carrying scientist” (in the words of Maine Coast Semester faculty Megan McOskar), Kimmerer’s writing represents what Klain calls a paradigm shift in environmental science.

“There is a growing recognition of how conservation as a movement has for too long looked down on, excluded or marginalized indigenous voices,” says Klain. “For decades, creating protected areas often entailed clearing indigneous people from the land. However, if you look globally, on average, land and water controlled by indigenous people have maintained more biodiversity than areas seized by colonists.”

While Kimmerer calls for indigenous wisdom to be elevated in our efforts to repair the landscape, she doesn’t position this type of knowledge as more important than another. Instead, indigenous knowledge is a critical strand among many that Kimmerer calls us to weave together into a strong and sturdy rope. As the prospect of mitigating climate change becomes more and more frayed against the immense weight of climate change and the politicization of the issue, it’s hard to argue that additional strength is not needed.

For Klain’s stewardship project at Boa Ogoi, this means weaving together the knowledge of many – some of whom may be surprising. Detailed ethnobotanical journals created by Mae Timbimboo Parry, a NWB of Shoshone elder and grandmother to Darren Parry, provide information about the sites’ once essential plant species. Interviews with local families furnish more recent data and a sense of the socio-economic influences that drive land-use decisions. Klain is also weaving in the work of other Utah State University students and faculty, including botanists, ecologists, habitat restoration specialists, and more.

Klain anticipates that Boa Ogoi will be a long-term collaboration between the NWBSN and Utah State University. She sees it as an opportunity to right a historical injustice and a way to connect indigenous students with research opportunities that align with their values. “There’s an educational gap when it comes to Native students in America. I see an important role for land grant institutions, including UMaine, USU, Cornell, and over one hundred others, to address this educational disparity more intensively,” says Klain, who also notes that land “grants” often consisted of acreage seized from Native peoples.

Kimmerer’s ideas are taking root on the other side of the United States, too. Maine Coast Semester faculty members point to her interdisciplinary approach as influential. “Kimmerer’s voice and approach to science captures an aspect of what we’re trying to teach at Chewonki,” says Sarah Rebick, an English faculty. “She speaks to the intersection of art, science, culture, and literature, underscoring that you can’t understand one discipline in isolation from another.”

Rebick recalls leading a discussion group on Braiding Sweetgrass with the six members of semester 65 who returned to Chewonki this spring as seniors (an option given to students whose on-campus experience was cut short by the pandemic last year). “Wendell Berry wrote that if you don’t know where you are, you don’t know who you are. We looked at lines from Braiding Sweetgrass that speaks to that,” says Rebick. Students ended the section by giving presentations on why Kimmerer’s book is important to read at this particular moment in history.

Natural History students are reading another Kimmerer book, an earlier work called Gathering Moss. “The average person can only name a handful of plants,” says McOskar. “Kimmerer writes that learning the names is the first step in regaining a connection.” Natural History students have long had to memorize the names of dozens of species; the science faculty now uses Kimmerer’s words to frame the importance of this task. “Her beautiful, eloquent writing affirms our ideas around the critical importance of natural history,” says McOskar.

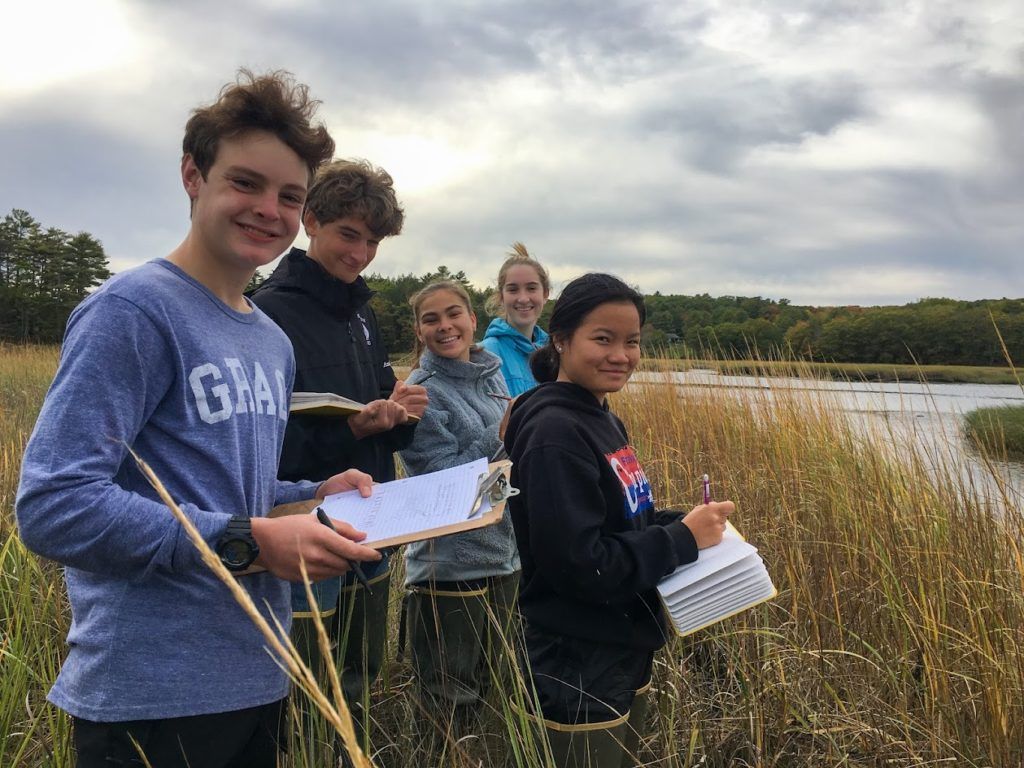

For most Maine Coast Semester students, Natural History and Ecology of the Maine Coast will be the only high school science class that brings them outside. “Traditional high school science focuses on biology, chemistry, and physics,” says McOskar. “And, with biology, the focus is on microbiology, not ecosystems.” Furthermore, traditional science often teaches a competitive framework where all ecological activity is rooted in self-interest. “Both modern research and indigenous knowledge point to a much more interconnected reality,” says McOskar.

Considering the climate crisis, it seems bizarre that ecosystem function doesn’t play a more significant role in high school learning. “Emphasis on abstract knowledge combined with the urban nature of most schools is really impactful,” says McOskar. “By the time a student reaches high school, their separation from the natural world is nearly complete.” McOskar’s class offers a counterpoint to this trend. “Everything we do, as a principle, is anchored in what students can directly experience,” she says. “Another thing that’s great about Kimmerer is that she’s based in the Adirondacks, so the species and ecosystems she writes about are familiar.”

“What is the right relationship between people and nature?” asks Klain. Indigenous voices like Kimmerer are helping us to see the answers more clearly. Instead of seeing plants and animals as commodities, Kimmerer presents us with a different paradigm. It’s not just the end product that sustains us – food, clean water, healthy trees, breathable air – but the act of tending itself.

“Most of us don’t think about our relationships with other people, pets or wild animals in terms of their economic value,” says Klain. “If we can begin applying relational values to the way we interact with nature more broadly, we can tap into fundamental drivers of human behavior.” Most crucially, reciprocity. “We need to ask – is this relationship feeding both of us?” says Klain. In being-to-being relationships, a symbiotic exchange is not just implied–It’s a requirement.

Back at Boa Ogoi, the NWBSN are using three principles to drive the design of their cultural interpretive center: reverence, resilience, and reconciliation. Klain hopes that the regenerated landscape will speak to these concepts. “This can be a prominent and transformative place,” she says. Indeed, Boa Ogoi has the potential to embody the new paradigm that Kimmerer expounds upon in Braiding Sweetgrass – that humans and the natural world are so closely twisted together that stewarding the earth is a fundamental way that we care for each other.

This article was originally written and published in January 2021.