If you’ve ever met former Chewonki President Don Hudson, it won’t surprise you to learn his retirement is busier than most people’s regular jobs. Hudson is fully engaged in conservation efforts across the state, serving as a volunteer for the Penobscot River Restoration Trust, the Gulf of Maine Council on the Marine Environment, Cornerstones of Science, and one more: the Town of Arrowsic’s Conservation Commission, for which he’s been busy counting alewives.

Alewives are a popular food for many other species including eagles, ospreys, gulls, loons, and terns; cod, haddock, striped bass, tuna, and brook trout; and whales, seals, otter, and turtles. So as the alewife population shrank in the 20th century due to hydroelectric dams, pollution, and badly designed culverts, the ecosystem as a whole suffered. Improved water quality, fish ladders at hydroelectric dams, and innovative fishways like the one in Arrowsic are giving alewives a second chance.

Alewives are a popular food for many other species including eagles, ospreys, gulls, loons, and terns; cod, haddock, striped bass, tuna, and brook trout; and whales, seals, otter, and turtles. So as the alewife population shrank in the 20th century due to hydroelectric dams, pollution, and badly designed culverts, the ecosystem as a whole suffered. Improved water quality, fish ladders at hydroelectric dams, and innovative fishways like the one in Arrowsic are giving alewives a second chance.

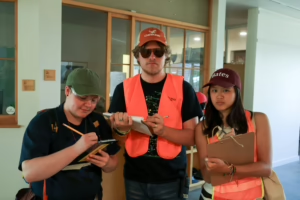

He is usually counting alongside his wife, Phine Ewing, a conservationist, botanist, and artist who played a key role in bringing an exemplary wildlife-safe culvert to Arrowsic’s Sewall Creek in 2014, replacing an old, damaged one that carried little water and had brought the local alewife migration to a virtual standstill. The new culvert has pools, weirs, and ramps within the creek as it passes under a road, allowing alewives and other fish, amphibians, and mammals to move freely in and out of 45-acre Sewall Pond, a historic alewife spawning site. Hudson and Ewing’s son Charlie Hudson, a videographer (and alumnus of Camp Chewonki, Wilderness Trips, and Maine Coast Semester 24), presents the story in his short documentary, “The Cool Little Culvert at Sewall Pond,” which you can watch here:

Hudson is helping track the impact of the new culvert on the alewife population. He counts the silvery fish as they struggle against the current to get back to their pond. The anadromous fish make their remarkable journey in May and early June, following rivers and streams to the lakes and ponds where they were born. The diminished Sewall Pond population had not only shrunk an important food supply for other creatures but had also caused phosophorous levels in the pond to rise, triggering algal blooms. Juvenile alewives remove phosphorous from water, absorbing it as they develop.

Hudson says the increase in alewives since the special culvert was installed has been breathtaking. “It’s fantastic,” he says, explaining that before the new culvert was installed four years ago, a negligible number of alewives were able to strugge through the old culvert. This year, Hudson, Ewing, and other volunteers have counted about 35,000 alewives reentering Sewall Pond.

What else is Don Hudson up to these days? “When I’m not being a serial volunteer,” he says, “I putter along with projects around our house. The plan is to finish the house before I die.” He also plans to walk the International Appalachian Trail in North America, in sections. “Phine says she’ll join me when it is not a forced march,” he quips. “We’ll be off to Prince Edward Island in October.”

What else is Don Hudson up to these days? “When I’m not being a serial volunteer,” he says, “I putter along with projects around our house. The plan is to finish the house before I die.” He also plans to walk the International Appalachian Trail in North America, in sections. “Phine says she’ll join me when it is not a forced march,” he quips. “We’ll be off to Prince Edward Island in October.”

His family commands much of his attention, too. “It is very nice to have sons Charlie and Reuben [also an alumnus of Camp Chewonki and Wilderness Trips, as well as a former Wilderness Trips leader] nearby and we’re always scheming to spend time with them and their significant others,” he says. His backyard beer brewing operation will start up again in the fall. And there’s a book somewhere in his head but “writing is taking a back seat right now.” It’s hard to write when you’re counting alewives.